Links about political prisoners of conscious, torture, etc

About political prisoners of conscious, torture, etc

ACTION ALERT NOTICE :

<> for more on these subjects, and newer material, please keep eyes and ears open!

Some links about political prisoners of conscious, torture, etc

http://www.dhafirtrial.net/about-this-site/about-dr-dhafir/

http://www.jubileeinitiative.org/FreeDhafir.htm

http://muslimprisonersupport.com/

http://www.muslimsforjustice.org/

http://www.freesamialarian.com

http://www.freeali.wordpress.com/

Especially about Solitary Confinement

http://solitarywatch.wordpress.com/

<>

<>

<> Daniel Patrick Boyd From Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Patrick_Boyd

<> Some of the “etc” of interest and for further investigation:

http://www.ifamericansknew.org/

<><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><>

And Lest We (not) Forget:

(Q. Who controls the past, present and future?)

Below: Abu Ghuraib [and these were called just a few “bad apples” (spoiling the others presumably)];

<>

<>

<> Oh,,, And remember this picture of the “Guard” at Abu Ghuraib prison in Iraq, but well of course they would be called as civilian “contractors” since the Israelis have lots of experience interrogating Palestinians in the Arabic Language and in enhanced techniques of interrogation, like eletrcity, water boarding, stress, and other torture techniques,,, etc.

<>

<>

<>

Ex-Bush Admin Official:

Many at Gitmo Are Innocent

ANDREW O. SELSKY / AP 19mar2009

SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico – Many detainees locked up at Guantanamo were innocent men swept up by U.S. forces unable to distinguish enemies from noncombatants, a former Bush administration official said Thursday. “There are still innocent people there,” Lawrence B. Wilkerson, a Republican who was chief of staff to then-Secretary of State Colin Powell, told The Associated Press. “Some have been there six or seven years.”

Wilkerson, who first made the assertions in an Internet posting on Tuesday, told the AP he learned from briefings and by communicating with military commanders that the U.S. soon realized many Guantanamo detainees were innocent but nevertheless held them in hopes they could provide information for a “mosaic” of intelligence.

“It did not matter if a detainee were innocent. Indeed, because he lived in Afghanistan and was captured on or near the battle area, he must know something of importance,” Wilkerson wrote in the blog. He said intelligence analysts hoped to gather “sufficient information about a village, a region, or a group of individuals, that dots could be connected and terrorists or their plots could be identified.”

Wilkerson, a retired Army colonel, said vetting on the battlefield during the early stages of U.S. military operations in Afghanistan was incompetent with no meaningful attempt to discriminate “who we were transporting to Cuba for detention and interrogation.”

Navy Cmdr. Jeffrey Gordon, a Pentagon spokesman, declined to comment on Wilkerson’s specific allegations but noted that the military has consistently said that dealing with foreign fighters from a wide variety of countries in a wartime setting was a complex process. The military has insisted that those held at Guantanamo were enemy combatants and posed a threat to the United States.

In his posting for The Washington Note blog, Wilkerson wrote that “U.S. leadership became aware of this lack of proper vetting very early on and, thus, of the reality that many of the detainees were innocent of any substantial wrongdoing, had little intelligence value, and should be immediately released.”

Former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and Vice President Dick Cheney fought efforts to address the situation, Wilkerson said, because “to have admitted this reality would have been a black mark on their leadership.”

Wilkerson told the AP in a telephone interview that many detainees “clearly had no connection to al-Qaida and the Taliban and were in the wrong place at the wrong time. Pakistanis turned many over for $5,000 a head.”

Some 800 men have been held at Guantanamo since the prison opened in January 2002, and 240 remain. Wilkerson said two dozen are terrorists, including confessed Sept. 11 plotter Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who was transferred to Guantanamo from CIA custody in September 2006.

“We need to put those people in a high-security prison like the one in Colorado, forget them and throw away the key,” Wilkerson said. “We can’t try them because we tortured them and didn’t keep an evidence trail.”

But the rest of the detainees need to be released, he said.

Wilkerson, who flew combat missions as a helicopter pilot in Vietnam and left the government in January 2005, said he did not speak out while in government because some of the information was classified. He said he feels compelled to do so now because Cheney has claimed in recent press interviews that President Barack Obama is making the U.S. less safe by reversing Bush administration policies toward terror suspects, including ordering Guantanamo closed.

The administration is now evaluating what to do with the prisoners who remain at the U.S. military base in Cuba.

“I’m very concerned about the kinds of things Cheney is saying to make it seem Obama is a danger to this republic,” Wilkerson said. “To have a former vice president fear-mongering like this is really, really dangerous.”

source: 31mar2009

http://www.foxnews.com/politics/2009/03/19/ex-bush-official-guantanamo-bay-innocent/

http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20090319/ap_on_re_la_am_ca/cb_guantanamo_wrongly_held/print

<>

<> And what about Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan, and so many others, and those even more notorious “black prisons” not ever seen, heard or mentioned in public?

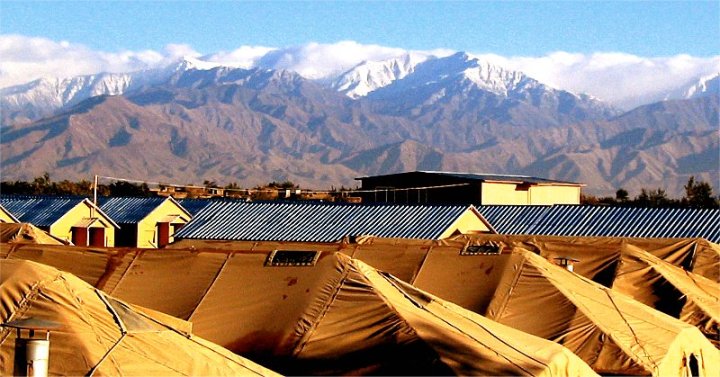

Below: Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan

Bagram >>> the Granddaddy of US terror camps!!!

<> Bagram: Obama’s Gitmo, only worse

<> Day 2: U.S. abuse of detainees was routine at Afghanistan bases

http://www.mcclatchydc.com/detainees/story/38775.html

<> Bagram – the granddaddy of US terror camps

<> This is a US torture camp

Evidence of prisoner abuse at Guantánamo is overwhelming – and it hasn’t made anyone safer

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2007/jan/12/comment.foreignpolicy

<> Afghanistan: Obama’s Camp Bagram Challenge

http://enduringamerica.com/2009/01/27/afghanistan-obamas-camp-bagram-challenge/

Pressure Rising on Obama to Address Bagram Prison

http://washingtonindependent.com/27518/pressure-rising-on-obama-to-address-bagram

<> US illegally detains more Afghans than ever at Bagram military base

http://www.wsws.org/articles/2008/jan2008/afgh-j09.shtml

< Torture Now an Afghanistan Issue

<> The Other Bad War: More Torture in Occupied Afghanistan

http://www.commondreams.org/views06/0302-31.htm

<>

Red Cross confirms ‘second jail’ at Bagram, Afghanistan

| By Hilary Andersson BBC News |

| Inmates from the old prison at Bagram have been moved elsewhere |

The US airbase at Bagram in Afghanistan contains a facility for detainees that is distinct from its main prison, the Red Cross has confirmed to the BBC.

Nine former prisoners have told the BBC that they were held in a separate building, and subjected to abuse.

The US military says the main prison, now called the Detention Facility in Parwan, is the only detention facility on the base.

However, it has said it will look into the abuse allegations made to the BBC.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) said that since August 2009 US authorities have been notifying it of names of detained people in a separate structure at Bagram.

“The ICRC is being notified by the US authorities of detained people within 14 days of their arrest,” a Red Cross spokesman said.

“This has been routine practice since August 2009 and is a development welcomed by the ICRC.”

The spokesman was responding to a question from the BBC about the existence of the facility, referred to by many former prisoners as the Tor Jail, which translates as “black jail”.

| ALLEGED ‘SECRET’ JAIL ABUSEBeatings by US soldiers during arrest

Prisoners deliberately prevented from sleeping Relatives not notified where detainees are held Lights kept on in cells at all times US denies abuse allegations |

“We are being notified about persons at the Bagram Theatre Internment Facility [now Detention Facility in Parwan] since Feb 2008,” the ICRC spokesman added.

In recent weeks the BBC has logged the testimonies of nine prisoners who say they had been held in the so-called “Tor Jail”.

They told consistent stories of being held in isolation in cold cells where a light is on all day and night.

The men said they had been deprived of sleep by US military personnel there.

In response to these allegations, Vice Adm Robert Harward, in charge of US detentions in Afghanistan, denied the existence of such a facility or abuses.

He told the BBC that the Parwan Detention Facility was the only US detention centre in the country.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/8674179.stm

<>

CIA Holds Terror Suspects in Secret Prisons

Debate Is Growing Within Agency About Legality and Morality of Overseas System Set Up After 9/11

In Afghanistan, the largest CIA covert prison was code-named the Salt Pit, at center left above.

(Space Imaging Middle East)

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/11/01/AR2005110101644.html

<> Black site From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_site

<> Ghost flights to black sites 27 February 2006, 05:25PM Mona Samari looks at the CIA’s use of rendition in the war against terror. Ghost flights The Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) extradition program—now commonly referred to as extraordinary rendition— involves removing suspects without court approval and rendering them to countries that have a record of torturing suspects in order to extract information… Black sites…Both Amnesty International’s Torture and Secret Detention: Testimony of the ‘Disappeared’ in the ‘War on Terror’ report and Human Rights Watch’s (HRW) Getting away with torture? report address the issue of rendering suspects to black sites….Torture by proxy… Such ‘disappearances’ often go hand-inhand with torture and other ill-treatment….

http://www.amnesty.org.au/hrs/comments/2185/

<> New account sheds light on CIA disappearances and ‘black sites’

http://www.amnesty.org.au/news/comments/10585/

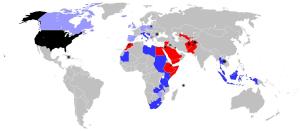

<> Mapping the black sites > Public Broadcasting interactive maps

Explore the interactive map to find out which countries are part of the CIA’s worldwide network of “black sites” and foreign prisons where the Agency has rendered dozens of terror suspects for “enhanced interrogations.” Also, see some of the U.S. front companies and aviation contractors whose planes have been used by the CIA to transport prisoners.

http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/rendition701/map/

<> Some of the whiter black sites since we know a little bit about them

The U.S. and suspected CIA “black sites” Extraordinary renditions allegedly have been carried out from these countries Detainees have allegedly been transported through these countries Detainees have allegedly arrived in these countries Sources: Amnesty International[31], Human Rights Watch, Black sites article on Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_site

<> Visiting A CIA ‘Black Site’ : from NPR: National Public Broadcasting

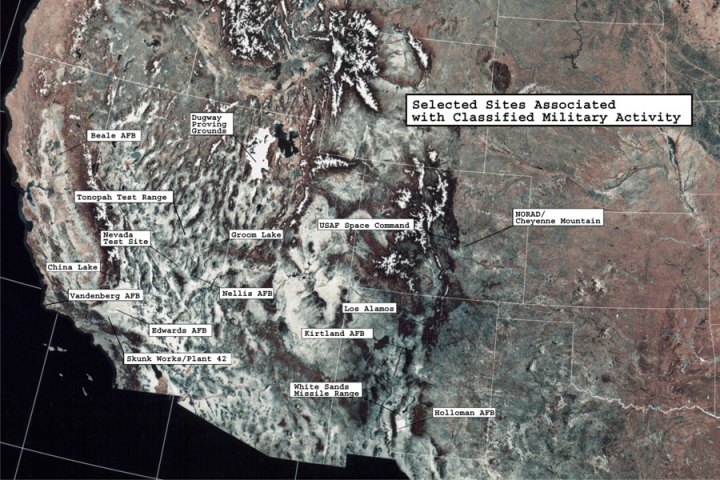

“… The U.S. government spends around $50 billion a year on covert activities. That’s according to Trevor Paglen. He’s the author of a book called “Blank Spots on the Map.”… secrecy involves creating spaces that are outside of the law but are outside the normal channels of oversight…. the larger that this secret world grows, the more that it bends the state in its own image, the more that it transforms the state around it to look more like itself….”

A map of black sites across the U.S. based on Trevor Paglen’s research. Courtesty Trevor Paglen

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=101867411

<> Chalmers Johnson and The “Blowback” trilogy

Johnson sees that the enforcement of American hegemony over the world constitutes a new form of global empire. Whereas traditional empires maintained control over subject peoples via colonies, since World War II the US has developed a vast system of hundreds of military bases around the world where it has strategic interests. A long-time Cold Warrior he applauded the collapse of the Soviet Union, I was a cold warrior. There’s no doubt about that. I believed the Soviet Union was a genuine menace. I still think so.[1] But at the same time he experienced a political awakening after the USSR 1989 collapse, noting that instead of demobilizing its armed forces, the US accelerated its reliance on military solutions to problems both economic and political. The result of this militarism (as distinct from actual domestic defense) is more terrorism against the US and its allies, the loss of core democratic values at home, and an eventual disaster for the American economy. The books of the trilogy are:

- Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire

- The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic

- Nemesis: The Last Days of the American Republic.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chalmers_Johnson

<> Obama’s Empire: An Unprecedented Network of Military Bases That is Still Expanding

|

| Picture Credit: Photobucket |

Barack Obama always said he would maintain for the US “the strongest military on the planet.” His national security team is committed to “rebuilding and re-strengthening alliances around the world to advance American interests and American security.” Today, with Obama as commander-in-chief, Washington is expanding its military base network. After the declaration of war on terror and right to pre-emptive war, the US military has an unprecedented global reach.

By Catherine Lutz Newstatesman July 30, 2009

<>

<>

<>

Below: new CIA HQ:

<> 100 Days To Restore The Constitution

http://ccrjustice.org/100-days-restore-constitution

and

on

and

on

See for yourself: search, seek, ask, reflect …

QUOTE:

“It is obligatory upon the Muslims to release their prisoners, even if it exhausts every penny of their wealth”

The renowned Muslim Jurist: Imam Malik bin Anas

<>

this below is old

As you all know she has unjustly been sentenced

to a zillion years

{-}

Aafia Siddiqui update :

Thursday May 6 NY, NY: court sentencing date

Planned Mass Mobilization For her Support

Protest the injustice and travesty of her trial!!!

A trial that Ignored the claims about Torture

and used outrageously questionable evidence,

while ignoring much clear evidence of her innocence.

WHY? Political motivations, goals.

Read about the time she spent

in prison under torture :

Read about the fact that two of her children

are still missing and

possibly were murdered.

<>

seek it for yourself (it ha more impact upon your soul) …. and you will receive

<>

JFAC Horrified by New Abuse Revelations,

Aafia Siddiqui Forced to Walk Naked Over the Qur’an

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

March 30th 2010

Contact: info@justiceforaafia.org

As hundreds of concerned citizens hold a Day of Remembrance in Pakistan to commemorate the seventh anniversary of her disappearance, the Justice for Aafia Coalition reveal for the first time, in the English language, specific harrowing details of the abuse Aafia Siddiqui was forced to endure in the years spent in secret detention.

During the course of an interview by Kamran Shahid on Pakistan’s Front Line, screened 26th March, Siddiqui’s mother and sister described publicly for the first time the various forms of torture she underwent at the hands of US agents. This included being:

- forcefully stripped by six men and then repeatedly sexually abused

- beaten with rifle butts until she bled

- bound to a bed, with her hands and feet tied whilst unspecified forms of torture were administered to the soles of her feet and head

- injected with unknown substances

- dragged by her hair

- having her hairs pulled out one by one

- forced to walk on the Qu’ran which had been desecrated in her cell whilst naked

Maryam Hassan, founder of the Justice for Aafia Coalition (JFAC), commented:

“These most recent horrific revelations shine a light for the first time on years of detention shrouded until now in darkness and mystery. Forced nudity, violent sexual abuse, the desecration of the Qu’ran, video-taped torture sessions have become infamous hallmarks of US detention since the start of the War on Terror, from Bagram to Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo.

The Obama administration must immediately disclose any video evidence in its possession relating to Ms Siddiqui’s detention and torture. The American public has a right to know what is being carried out in its name as much as the Pakistani public are deserving of knowing the horrendous abuse one of their citizens has been subjected to. “

For the full interview, transcribed and translated into English by the

Justice for Aafia Coalition, please visit:

To view the video recording of the interview in Urdu:

http://justiceforaafia.org/index.php/multimedia/475-aafia-siddiqi-front-line-special-program-26th-march-2010

<>

Other recent updates

Open Letter to US Attorney from Tarek Mehanna Support Committee

***Please forward***

On Friday, March 12, members of the Tarek Mehanna Support Committee attempted for the second time to meet with a representative of the Massachusetts US Attorney’s office. Again we were told to fill out a complaint form–there was no one at the office who could speak to us. We asked whether it was the explicit policy of the new US Attorney not to meet with concerned members of the public. The “Administrative Specialist” insisted that this was not the policy of the office, but couldn’t explain why our calls, faxes and our formal complaint remained unanswered.

This time we left a written statement and directed the administrative assistant to bring it to the attention of the US Attorney. We were told, once again, that someone would contact us on Monday.

Many of us had thought that the former Massachusetts US Attorney Michael Sullivan had set a low water mark for unresponsiveness to community concerns. It seems that the new holder of the office, Carmen Ortiz, may lower the bar still further.

We are releasing our statement as an open letter to the new US Attorney.

=================

United States Attorney Carmen Ortiz

John Joseph Moakley

United States Federal Courthouse

1 Courthouse Way, Suite 9200

Boston, MA 02210

Friday, March 12, 2010

US Attorney Carmen Ortiz:

We are here representing the Tarek Mehanna Support Committee.

During the week of February 22 through February 26 we made numerous phone calls and sent faxes to Assistant Attorney Chakravarty to express strong community concerns in the case of Tarek Mehanna. Chakravarty appears to have dealt with these concerns by disabling his voicemail, routing calls to the voicemail of a secretary who never returned them. As you may have been informed, we sent a delegation to your office on Friday, February 26, to raise our concerns in person. We were instructed to fill out a complaint form with our contact information so that we could arrange an appointment with you. Since then, no one from your office has contacted us.

In our conversation with your administrative assistant, we expressed our belief that the unresponsiveness of your office to community concerns shows an arrogant contempt for the residents of Massachusetts. This contempt is especially egregious in light of the history of severe prosecutorial misconduct that has come to characterize the Massachusetts US Attorney’s office from the time of Sullivan’s leadership.

We are here again to demand that you take our concerns seriously.

We believe that Tarek Mehanna is the victim of FBI retaliation and severe institutional abuse of power because of his refusal to act as an informant for the FBI–a refusal that lies fully within his constitutionally protected rights. The FBI explicitly threatened Mr. Mehanna with this retaliation, saying that they would make his life a “living hell,” by using false allegations of “terrorism” unless he agreed to act as an informant within the Muslim community.

These FBI threats and the decision of the US Attorney’s office to carry them out are reminiscent of the criminal collaboration between Assistant US Attorney Jeffrey Auerhahn–also responsible for Mr. Mehanna’s prosecution–and FBI Special Agent Michael Buckley, documented in the case Ferrara v. US.

Auerhahn’s record of conduct would merit not merely disbarment, but criminal sanctions. These practices include:

*Coercing a witness into giving false testimony (suborning perjury);

*Falsifying evidence;

*Withholding exculpatory evidence from defense;

*Lying before the court (perjury).

US Attorney Michael Sullivan’s failure to sanction Auerhahn for these practices in any meaningful way speaks of complicity in this criminal misconduct at the highest level of the Massachusetts office. As the allegations against Auerhahn came to light, rather than suspending Auerhahn, Sullivan transferred him from the Racketeering Unit to the Anti-Terrorism Unit, where he has continued in the same practices against another set of victims.

The criminal collaboration between Auerhahn and FBI agent Buckley requires that your office not only take action against Auerhahn, but reconsider those pending cases in which Auerhahn has been involved.

We believe that Tarek Mehanna is another innocent victim of illegal practices on the part of the FBI and the US Attorney’s office. We strongly urge you, as the new leader of the Massachusetts US Attorney’s Office, to break with this atrocious history.

Sincerely,

The Tarek Mehanna Support Committee

<>

One Day We’ll All Be Terrorists By Chris Hedges

December 28, 2009 “Truthdig“

| More Click on “comments” below to read or post comments

Comments that include profanity or personal attacks or other inappropriate comments or material will be removed from the site. Additionally, entries that are unsigned or contain “signatures” by someone other than the actual author will be removed. Finally, we will take steps to block users who violate any of our posting standards, terms of use or privacy policies or any other policies governing this site. See our complete Comment Policy and use this link to notify us if you have concerns about a comment. We’ll promptly review and remove any inappropriate postings. You are fully responsible for the content that you post. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. Information Clearing House has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is Information ClearingHouse endorsed or sponsored by the originator.) |

<><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><>

<>

Americans Held in Pakistan Allege FBI Abuse

i.e. they say they are being tortured, set up,

and kept away from Media, Families, Lawyers

See the AP video exposing their cry for help

and their note thrown from the vehicle

while being transported to court

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yvozOBLSPGs

<> Aafia Siddiqui maintains her innocence

Siddiqui continues to say that the charges against her are fabricated

Mystery of Siddiqui disappearance

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/7544008.stm

Pakistani woman denies shooting US Afghan soldiers

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/8467832.stm

<> About her testimony

THE PEACE AND JUSTICE FOUNDATION

11006 Veirs Mill Rd, STE L-15, PMB 298 Silver Spring, MD. 20902

SAFAR 1431 A.H. (January 31, 2010)

THE POWERFUL TESTIMONY OF Dr. Aafia Siddiqui

Aafia Siddiqui – a daughter, a sister, a mother of three, committed Muslim, social scientist, hafiz of Qur’an – needed to be heard. For years she had suffered in virtual silence…aching to be heard, to be understood, to have certain malicious untruths corrected and exposed for the lies they were. That day finally came on Thursday, January 28, 2010!

The high drama of that day’s proceedings revolved around the question of whether or not U.S. District Judge Richard Berman would grant Aafia’s repeated demand to take the stand in her own defense.

Aafia’s lawyers appeared to be animate in their opposition to her taking the stand, while the prosecution appeared (on the surface) to be in favor of Aafia being entitled to her Fifth Amendment right. Her brother (Muhammad) was apprehensive about her taking the stand, leaning more in favor of her following the advice of her lawyers. Even Pakistani Ambassador Hussain Haqqani became involved. During a short visit he was allowed with the defendant, he reportedly advised Aafia to follow the advice of her lawyers.

Aafia’s response to this collective concern was that she would make istiqara (a supplication to ALLAH Almighty for guidance on the matter); and in the end Aafia Siddiqui would be heard.

While I understood the reservations of those who were concerned about Aafia taking the stand (given all that she had already been through), I fully supported our sister’s right to be heard, and was guardedly optimistic about the potential outcome. More than anything, however, I knew that Aafia – like two young Muslim men in an Atlanta courtroom, and several young Muslim men in a New Jersey courtroom (who were eager, but manipulated into not taking the stand in their own defense not long ago) – needed to be heard! Aafia needed to have her day in court!

The process began with a preliminary (test) examination, with Aafia taking the witness stand in the absence of the jury – a kind of hearing within a hearing – to see how she would respond to that type of intensive and focused examination. After the judge determined that she was capable enough to enjoy her constitutional “right” to take the stand in her own defense, the jury was brought back into the courtroom, and it was on. (And what truly spectacular courtroom drama it turned out to be!)

The following summary is based on my notes from January 28th

Open court proceedings began late in the morning, due to a number of procedural issues that needed to be addressed behind closed doors. Once proceedings began, it did so with the judge explaining Aafia’s right, and the possible risks, of her taking the stand. There was extensive discussion about the course and extent of cross examination should Aafia decide to testify.

The government’s support of Aafia taking the stand was full of irony, given the fact that the government had repeatedly argued (during pre-trial and trial proceedings) that Aafia should not even be allowed to remain in the courtroom, because of her periodic outbursts and “uncontrollable” nature (in their view).

The First Witness

It was noted by the government that over a 12 day period, while Aafia was at the Craig Field Hospital at Bagram for critical care medical treatment, following her near fatal re-arrest in July 2008, two FBI agents had continuous access to the injured prisoner (a male and female who did not identify themselves to Aafia as FBI personnel).

FBI Special Agent Angela Sercer was the first to testify. She spoke about how she interrogated Aafia on a daily basis for the purpose of gathering “intelligence.” She described how she sat with Aafia for an average of eight hours each day, and of how they discussed the shooting incident and other related matters (discussions she said Aafia would always initiate). Agent Sercer prepared written reports, and disclosed during testimony that Aafia was never Mirandized (i.e. informed of her rights to remain silent and consult with an attorney before questioning) , nor did she have access to a Pakistani consular official.

According to Sercer, Aafia mostly enjoyed her discussions with this special agent. Sercer maintained that she treated Aafia with respect and did her best to respond to Aafia’s needs – i.e. when she requested food, water, bathroom access, or when she requested a Qur’an and a scarf, or when she would complain that the “soft restraints” were too tight and needed to be loosened, etc.

Between 7/19/-8/4/08, FBI agents were posted inside and outside Aafia’s room 24 hours a day, ostensibly to insure that Aafia could not escape and to provide security for hospital personnel – despite the “soft restraints” which secured her hands and legs to the bed (in what Aafia later described as very uncomfortable positions) during her stay at this field hospital in Bagram.

The second witness

The second agent to testify was FBI Special Agent Bruce Kamerman, who had reportedly been assigned on 7/21/08. He claimed that Aafia made numerous statements, that she seemed lucid and to not be in much pain. He also insisted that there was never any coercion. He testified that Aafia had no visitors, and that no Afghan staff attended to her. He also claimed that there were occasions when Aafia would declare that her children were dead, and other times when she stated they might be living with her sister.

Following the testimony of the second agent, a hearing within the trial was held so that Aafia could give testimony (in the absence of the jury).

Aafia testified that when she first realized she was in a hospital she had tubes everywhere. She was in a narcotic state resulting from the administration of powerful drugs (one or two she could remember by name, others she couldn’t). She recalled how her hands and feet were secured uncomfortably apart. She said the agents never identified themselves as FBI, except for “Mr. Hurley.”

Aafia accused Agent Bruce Kamerman of subjecting her to “psychological torture.” She accused him of being immodest whenever he was present and medical personnel needed to examine her, and complained of how he would stand right outside the bathroom door whenever she needed to use it. She testified that Kamerman would sometimes come in the middle of the night (when he wasn’t supposed to be there), and encourage the person assigned to take a break. Aafia said she remained in a sleep deprived state as a result of his frequent presence.

During this period she never had any contact with family, nor with any Pakistani authorities. She thought that [FBI Agent] “Angela was just a nice person.”

During the cross examination Aafia spoke about being “tortured in the secret prison,” and of how she kept asking about her children. She insisted that she never opined that they might be with her sister.

(I should note here that Aafia’s testimony was consistent with information contained on an audio CD that we’ve produced on the case. On the CD, former Bagram and Guantanamo prisoner Moazam Beg recounts how the un-identified female prisoner at Bagram, known only as Prisoner 650, was identified as a Pakistani national who appeared to be in her 30s, and as someone who had been torn away from her children and who didn’t know where they were.)

Aafia also testified that she had multiple gunshot wounds; and that in addition to the gunshot wounds she had a debilitating back condition (resulting from being thrown on the floor after she was shot), persistent headaches, and an intubation tube. She also emphasized that she was in and out of consciousness; and, at times, mentally incoherent.

The video testimony of an Afghan security chief (by the name of Qadeer) was received by the court. While I had to briefly leave the court, and missed this testimony, it is my understanding that what Qadeer had to say about events at the Afghan National Police station in Ghazni – leading up to the shooting of Aafia – contradicted the testimony of a number of the government’s main witnesses.

Later in the afternoon, when Aafia testified in front of the jury, the overflow courtroom (where I was seated) was full of observers. The majority appeared to be non-Muslims in professional attire – a probable mix of court and Justice Department personnel (including interns), law students, and a few journalists. I would estimate that roughly a quarter of the observers in this overflow courtroom were made up of solid Aafia supporters – and yet the reaction to the testimony at times was both interesting and edifying.

When I returned to the courtroom (about 10 minutes into Aafia’s testimony), she was describing her academic work leading up to the achievement of her PhD at Brandeis University. She testified that after completing her doctorate studies she taught in a school, and that her interest was in cultivating the capabilities of dyslexic and other special needs children.

During this line of questioning, the monstrous image that the government had carefully crafted (with considerable support from mainstream media) of this petite young woman, had begun to be deconstructed. The real Dr. Aafia Siddiqui – the committed muslimah, the humanity-loving nurturer and educator, the gentle yet resolute mujahid for truth and justice – began to emerge with full force.

Testimony then proceeded to the events of July 17-18, 2008. Aafia testified that she remembered being concerned about the whereabouts of her missing children. She also remembered a press conference in an Afghan compound.

She testified about being tied down to a bed until she vigorously protested, and was later untied and left behind a curtain. She later heard American and Afghan voices on the other side of the curtain, and concluded that they [Americans] wanted to return her to a “secret prison” again. She testified about how she had pleaded with the Afghans not to let the Americans take her away.

She testified about peaking through the curtain into the part of the room where Afghans and Americans were talking, and how when a startled American soldier noticed her, he jumped up and yelled that the prisoner had gotten loose, and shot her in the stomach. She described how she was also shot in the side by a second person. She also described how after falling back onto the bed in the room, she was violently thrown to the floor and lost consciousness.

She testified that she was in and out of consciousness, and vaguely recalled being placed on a stretcher, a helicopter, and receiving a blood transfusion – which she protested, drawing laughter in the courtroom when she recounted how she had “threatened to sue” her medical attendants if they gave her a blood transfusion. During this testimony, Aafia animatedly rejected the allegation that she picked up a [M-4] rifle and fired it (or that she even attempted to do so).

The Cross Examination

This is the time when every eye and every ear was riveted on the proceedings. It was the moment that Aafia’s defense attorneys, her brother, and a host of Muslim and non-Muslim supporters (seated within both courtrooms) dreaded. It was also the point in the proceedings that had the prosecution salivating for what opportunities would come there way – or so they thought!

Cross examination began with Aafia revisiting the degrees that she received at MIT and Brandeis universities. She acknowledged that she took a required course in molecular biology; but emphasized that her work was in cognitive neuroscience. When questioned on whether she had ever done any work with chemicals, her response was, “only when required.”

(This opening line of questioning was significant for its prejudice producing potential in the minds of jurors. While Aafia is not being charged with any terrorism conspiracy counts, the threat of terrorism has been the pink elephant in the room throughout this troubling case!)

The prosecutor attempted to draw a sinister correlation between Aafia and her [then] husband being questioned by the FBI in 2002, and leaving the U.S. a week later. Aafia noted that there wasn’t anything sinister about the timing; they had already planned to make that trip home before the FBI visit. To underscore this point, she noted how she later returned to the U.S. to attempt to find work in her field.

One of the most heart-wrenching moments in the cross-examination was when Aafia described how she was briefly re-united with a young boy in Ghazni (July 2008) who could have been her oldest son. She spoke of how she was mentally in a daze at that time, and had not seen any of her children in five years. As a result she could not definitively (than or now) determine if that was indeed her son, Ahmed.

When asked whether she had incriminating documents in her possession on the day she was arrested, Aafia testified that the bag in her possession on the day that she was re-detained was given to her. She didn’t know what was in the bag, nor could she definitively determine if the handwriting on some of the documents was hers or not. She also mentioned on a number of occasions (to the chagrin of the prosecutor) how she was repeatedly tortured by her captors at Bagram.

She was also questioned on whether she had taken a pistol course at a firing range while a student in Boston. Her initial reaction was that she did not have any recollection of taking such a course, and when pressed further, answered “No.” When the prosecutor continued to press the issue (infusing sinister motivations in the process), Aafia admonished the prosecutor in the strong, clear voice that was heard throughout her testimony: “You can’t build a case on hate; you should build it on fact!”

Aafia testified that all she was thinking about at the time of her re-arrest in Ghazni, was “getting out of that room and not being sent back to the secret prison.” While discussions were going on between the Afghans and Americans, Aafia was searching for a way out. She repeated her assertion that she startled one of the soldiers who hollered, “She’s free! – before shooting her.

Aafia also elicited an approving reaction in the courtroom when she opined, in reaction to the government’s narration of events, she could not believe a soldier would be so irresponsible as to leave his M4 rifle on the floor unsecured.

In response to government questioning she again took the opportunity to strongly rebuke Agent Kamerman, while rejecting most of his testimony revisited by the prosecutor.

Aafia spoke highly of a number of nurses (and a doctor) who took care of her at Bagram. There was one nurse in particular that Aafia promised to mention favorably if she ever wrote a book. She then produced laughter in the courtroom again when she stated, “Since I don’t think I’m going to write a book, I’m mentioning her now.”

One of the most powerful and revealing moments in the testimony was when she spoke about the people who systematically abused her in the “secret prison” – denouncing them as “fake Americans, not real Americans.” (Because of the way their actions both violated and damaged America’s image!)

She spoke again, under cross examination, about the strong pain medication she was on, and some of the effects this medication had on her.

Aafia also mentioned how she was instructed to translate and copy something from a book while she was secretly imprisoned. During the course of this testimony which repeatedly drew the ire of an increasingly frustrated prosecutor, Aafia noted how she can now understand how people can be framed (for crimes they are not guilty of).

At this point in the proceedings, the judge ordered a brief recess. Clearly the government had thought that they would be able to control and manipulate Aafia in manner that would work in their favor; this ended up being a MAJOR MISCALCULATION. The purpose of this break in the proceedings, in my humble opinion, was to allow the prosecutor to regain her composure, and consult with fellow prosecutors for a more effective line of attack.

When testimony resumed, Aafia spoke of how she was often forced-fed information from one group of persons at the secret prison, and then made to regurgitate the same information before a different group of inquisitors. While it was presented to her as a type of “game,” she spoke of how she would be “punished” if she got something wrong.

On defense cross, Aafia was shown pictures and asked to identify herself in them. She reluctantly did so, but with a little levity, citing how unattractive and immodest the photos were.

I could not see the photos from the overflow courtroom where I was sitting, but I assume that these were the photos of an un-covered, emaciated and emotionally disfigured Aafia Siddiqui – after her horrific ordeal at the hands of American terrorists.

A final note: I sincerely believe that Aafia Siddiqui’s time spent on the witness stand on January 28th was a cathartic experience for her – but one that the prosecution, in retrospect, now deeply regrets. For any truly objective and fair-minded person who witnessed that day’s proceedings, the U.S Government’s case against Aafia Siddiqui was exposed for what it always was…a horrific and profoundly tragic miscarriage of justice!

The struggle continues…

El-Hajj Mauri’ Saalakhan © copyright 2010, All Rights Reserved

(Permission is granted to forward or publish this information as is, and with the appropriate attribution. )

PROCEEDINGS RESUME AT 9 AM TOMORROW

MONDAY MORNING

500 Pearl Street in lower Manhattan

Court of Judge Berman

<>

<>

<> Yvonne Ridley discusses the Aafia Siddiqui Case

Yvonne Ridley discusses the Aafia Siddiqui Case

http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article24566.htm

“Shock, Horror, Drama” That You Won’t Read In The New York Times

By Yvonne Ridley in New York

February 02, 2010 “Information Clearing House” — Dr Aafia Siddiqui is a bright, intelligent woman who has been through hell having being kidnapped, tortured in secret prisons, gunned down by US soldiers and renditioned to America where she is now facing attempted murder charges against those who shot her .

Only in the cock-eyed crosshairs of George W Bush’s War on Terror could this happen and I hope to God that the jurors who will go through the evidence during the next few hours, if not days, see through this rotten legacy and recognise the case for what it is … a tissue of lies enveloped in a web of deceit.

The last seven years of Dr Aafia’s life could have been penned by a Hollywood scriptwriter, but instead all the folk from Tinsel Town could come up with was the rather tame blockbuster movie Rendition starring Reese Witherspoon.

But several days ago those of us following the case closely were given a glimpse into the dark, mysterious world in which Dr Aafia has been forced to live since 2003.

And more importantly the details were relayed in a hushed court not by any lawyer, but by the only person qualified to talk with any authority about dark prisons, interrogations and abuse – the account relayed to the courtroom in Manhattan, New York came from the mouth of Dr Aafia herself.

Running for more than two weeks there’s been little or no record in the Western media of this shocking case other than some of the most ill-informed, embarrassingly skewed reports which indicate the noble profession of journalism is still in a narcotic malaise in the Big Apple.

That the New York Times had to apologise to its readers on the front page for selling them short on the build up to and the unfolding war in Iraq, one would have thought would have had an impact on the quality of future output.

That the US press corps, with the exception of The Baltimore Sun, had to play catch up after ‘missing’ the Abu Ghraib scandal speaks volumes.

Sadly it seems that huge swathes of the US media have learned nothing.

Just a few days ago an embarrassing wealth of riches in terms of soundbites which would have had most journalists salivating like a Pavlov Dog came tumbling out in the lower Manhattan court.

But like a gaggle of bald men fighting over a comb, the scribes present in the main courtroom could only focus on one irrelevant detail … Dr Aafia Siddiqui had fired a pistol at a gun club. Excuse me? This is America … where half the adult population live in houses where guns are kept. Let’s keep it real – America has 80 million gun owners with a total of 258 million guns.

Possibly the most wronged woman in the entire War on Terror had just revealed how she was held in secret prisons, with no legal representation, cut off from the outside world since 2003 where brutal interrogation techniques were used to break her down. And, to make matters even worse when she was kidnapped from her home city in Karachi, Pakistan her three children were also snatched … the fact two of those children are American citizens held no sway with the majority of the assembled press corps. One wondered if their pants had caught fire if they would have even smelled the smoke.

And so what held the Western media attention? Well, it transpired that Dr Aafia may have taken a pistol shooting course as part of her curriculum in an American university. That’s a bit like an American tourist ordering fish and chips and a cup of tea on arrival in Britain. Hold the front page!

So for your benefit, let me tell you about the real “shock, horror, drama” that you won’t read in the New York Times or the rest of the corporate media.

After two weeks of being baited and defamed, in a calm, articulate and precise manner Dr Aafia Siddiqui finally had her day – and her say – in court.

It should have been a moment of schadenfreude for the prosecution team as they prepared to sit back and enjoy the spectacle of the defendant rant and rave like a mad woman when she decided on her right to take the stand.

Perhaps Judge Richard Berman, a modest little man with much to be modest about, must have thought his rather unremarkable legal career would finally make more than just the current footnote in Wikipedia.

Most of her own legal team watched mortified in the belief that their reluctant client (she had dismissed them publicly many times to no effect) might destroy the robust defence they had built over two weeks.

Even her brother Muhammad, who has sat in court everyday watching and listening to the proceedings told me he wondered if his little sister was making the right decision.

Given the chance, I think I would have also advised her against speaking.

Well thank goodness Dr Aafia ignored us all – within minutes of giving evidence the prosecution wanted to shut her up, Judge Berman looked like he was sucking on the bitterest of lemons and the rest of the courtroom sat back aghast.

The Pakistan media, despatched into one of the two overspill rooms frantically scribbled down their notes so as not to miss one single word and her supporters sat back aghast watching a breathtaking spectacle.

One of the few community leaders who has been outstandingly vocal in his support, El-Hajj Mauri’ Saalakhan, probably expressed himself better than any of the nitwits sleeping on the press benches when he wrote: “She testified that after completing her doctorate studies she taught in a school, and that her interest was in cultivating the capabilities of dyslexic and other special needs children.

“During this line of questioning, the monstrous image that the government had carefully crafted (with considerable support from mainstream media) of this petite young woman, had begun to be deconstructed. The real Dr Aafia Siddiqui – the committed muslimah, the humanity-loving nurturer and educator, the gentle yet resolute mujahid for truth and justice – began to emerge with full force”.

As the evidence continued we learned that she didn’t know where her three children were – it was sensational content. She talked of her dread and fear of being handed back to the Americans when she was arrested in Ghazni and was held by police.

Terrified that yet another secret prison was waiting for her she revealed how she peaked through the curtain into the part of the room where Afghans and Americans were talking, and how when a startled American soldier noticed her, he jumped up and yelled that the prisoner was loose, and shot her in the stomach. She described how she was also shot in the side by a second person. She also described how after falling back onto the bed in the room, she was violently thrown to the floor and lost consciousness.

This ties in exactly with what I was told by the counter terrorism police chief I interviewed in Afghanistan back in the autumn of 2008 – I remember him laughing as he told me how the US soldiers panicked, shot and most of them ran out of the room in a panic. Hmm, no wonder the prosecution didn’t want him giving evidence in court.

Instead they chose to record his interview and voiced it over with a shoddy translator who has a long distance relationship with the Pashtu language … defence team take note. Demand a real Pashtu translation because what was given out in court was misleading and not the words of the actual words of police chief – don’t take my word for it … speak to someone whose first language is Pashtu. it’s hardly rocket science.

Of course there’s no way a bunch of soldiers are going to admit they lost it, but according to those I interviewed for my film In search of Prisoner 650 in Afghanistan that’s exactly what happened.

But let’s return to Aafia and the cross examination which followed. When questioned on whether she had ever done any work with chemicals, her response was, “only when required.”

As Mauri remarked: “This opening line of questioning was significant for its prejudice producing potential in the minds of jurors. While Aafia is not being charged with any terrorism conspiracy counts, the threat of terrorism has been the pink elephant in the room throughout this troubling case!”

The prosecutor attempted to draw a sinister correlation between Aafia and her now ex-husband being questioned by the FBI in 2002, and leaving the US a week later. Aafia noted that there wasn’t anything sinister about the timing; they had already planned to make that trip home before the FBI visit. To underscore this point, she noted how she later returned to the US to attempt to find work in her field.

Mauri said one of the most heart-wrenching moments in the cross-examination was when Dr Aafia described how she was briefly re-united with a young boy in Ghazni (July 2008) who could have been her oldest son. She spoke of how she was mentally in a daze at that time, and had not seen any of her children in five years. As a result she could not definitively (then or now) determine if that was indeed her son, Ahmed.

When asked whether she had incriminating documents in her possession on the day she was arrested, Aafia testified that the bag in her possession on the day that she was re-detained was given to her. She didn’t know what was in the bag, nor could she definitively determine if the handwriting on some of the documents was hers or not. She also mentioned on a number of occasions (to the chagrin of the prosecutor) how she was repeatedly tortured by her captors at Bagram.

But the killer blow was delivered when Dr Aafia mildly challenged the prosecutor in a calm, crystal clear voice that was heard throughout her testimony: “You can’t build a case on hate; you should build it on fact!”

There were other sensation moments and revealing testimony and if anyone thought that she hated Americans she removed that idea from their minds when she talked of the “fake Americans, not real Americans” who held and tortured her in the secret prisons. They were fake, she explained because real Americans would not behave in such a way to bring shame on their country.

We also discovered how she was instructed to translate and copy something from a book while she was secretly imprisoned. During the course of this testimony which repeatedly drew the ire of an increasingly frustrated prosecutor, Aafia noted how she can now understand how people can be framed (for crimes they are not guilty of).

It all got too much for Judge Berman who ordered a brief recess.

The plan to goad and incite Dr Aafia to perform some incomprehensible, demonic rant had back-fired.

When testimony resumed, we learned through the star witness how she was often forced-fed information from one group of persons at the secret prison, and then made to regurgitate the same information before a different group of inquisitors. While it was presented to her as a type of “game,” she revealed of how she would be “punished” if she got something wrong.

Now, more than ever, this trial should be brought to an end. And if Judge Berman wants to go down in history for punctuating his lack lustre career as a member of the judiciary for standing up in the cause of truth and justice now is the time to do it.

The truth will out and the US Government’s case has been exposed for what it is … a sham.

And it is a fitting tribute to the endurance of Dr Aafia, mother-of-three, that the sham has been exposed by her.

Let’s see justice being carried out in 500 Pearl Street in lower Manhattan tomorrow. Over to you, your Honour Judge Berman.

The ‘Hole’ Truth:

Defense says ‘Terror Mom’ did not Shoot at Soldiers

By BRUCE GOLDING

February 01, 2010 “New York Post” — Lawyers for accused “terror mom” Aafia Siddiqui pulled a classic “gotcha” during closing arguments today, producing video evidence that two purported bullet holes were present in a police station wall a day before she allegedly shot at Americans there.

“The government says you can’t press ‘pause’ in this case, but you can, because we have the video and we pressed ‘pause,’” lawyer Linda Moreno said as jurors looked at a still frame from a televised news conference after Siddiqui’s July 2008 arrest.

Two small holes that prosecution witnesses earlier said could have been gunshot damage from an assault rifle that Siddiqui allegedly fired were clearly visible in the background.

Moreno said the “non-existence of physical evidence” proved that Siddiqui never shot the weapon — which a Special Forces warrant officer set down on the floor — and that instead “she startled the soldier in front of her and got shot” after peeking around a curtain in the back.

“Who doesn’t believe that if Aafia Siddiqui picked up that weapon and fired into the room she wouldn’t have been shot dead?” Moreno said.

She also accused the prosecution of using “scare” tactics to try and convict the Siddiqui — who refused to attend the closings — by repeatedly focusing on hand-written plans for a “mass casualty” attack on New York City that were seized from the alleged al Qaeda associate after she was busted as a suspected suicide bomber.

Prosecutor David Rody countered that the terror plans showed Siddiqui’s “extreme desire to attack Americans” and said the absence of damage from the rounds she allegedly fired didn’t get the 37-year-old neuroscientist off the hook.

Rody said Siddiqui’s rounds could have struck furniture that was removed sometime after the incident and before an FBI investigator was able to inspect the scene six days later.

“Forensic science is an imperfect tool in this circumstance….You don’t have a good enough physical or photographic record of that room to know where the damage is,” Rody argued in Manhattan federal court.

He accused Afghan personnel of hiding two M-4 shell casings from the scene to cover up the “terribly embarrassing incident” in which they left Siddiqui free behind the curtain without telling the Americans who showed up to interrogate her.

Rody also compared Siddiqui’s “ridiculous, obvious lies” with the testimony of six prosecution eyewitnesses who said they saw her fire the rifle.

“Do you believe her when she lied to your face?” he asked, referring to Siddiqui’s claim that she didn’t take firearms training in college.’

He also downplayed differences in the various eyewitness accounts, saying “those inconsistencies are the hallmark of truth” and proved that they witnesses didn’t conspire to frame the defendant.

The jury is expected to get the case and start deliberations by the end of today.

Background on this case here

<>

<>

Will Siddiqui Trial Reveal U.S. Rendition and Torture? – TIME

Once one of the most wanted women in the world, Aafia Siddiqui is at the … has in the worst instances amounted to nothing less than torture by proxy. …

www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1954598,00.html

<>

<>

<>

Mystery of ‘ghost of Bagram’

– victim of torture or captured in a shootout?

Mother of three in court after five-year disappearance ends in Afghanistan amid conflicting claims

“…Siddiqui’s sister, Fauzia, said she had been raped and tortured. “Her rape and torture is a crime beyond anything she was accused of,” she said. “This is the real crime of terror here.” She pleaded for the child who was with her sister when she was captured, according to the American authorities, to be immediately handed over to the family. It is unclear what has happened to the other two children….”

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/aug/06/pakistan.afghanistan

<>

<>

<>

Guantánamo “Suicides” exposed to be Murder,

then huge cover-up!!!

…. (but who’s reading, seeing ,listening, acting)

The Guantánamo “Suicides”:

A Camp Delta sergeant blows the whistle

By Scott Horton

http://www.harpers.org/archive/2010/01/hbc-90006368

<>

Four US soldiers cast doubt on Gitmo ’suicides’

By Daniel Tencer

Monday, January 18th, 2010 — 1:17 pm

Four members of a US military intelligence unit assigned to Guantanamo Bay are questioning the government’s official version of the deaths of three detainees in the summer of 2006.

The soldiers are offering a very different version of events than the one provided by the official report carried out by the Naval Criminal Investigation Service. Their stories suggest the three inmates may not have killed themselves — or, at least, not in the way the US military claims.

“All four soldiers say they were ordered by their commanding officer not to speak out, and all four soldiers provide evidence that authorities initiated a cover-up within hours of the prisoners’ deaths,” reports Scott Horton at Harper’s magazine.

According to the US Navy, Gitmo detainees Salah Ahmed Al-Salami, Mani Shaman Al-Utaybi and Yasser Talal Al-Zahrani were found hanged in their cells on June 9. 2006. The US military initially described their deaths as “asymmetrical warfare” against the United States, before finally declaring that the deaths were suicides that the inmates coordinated among themselves.

But a report from Seton Hall University Law School, released last fall, cast doubt on almost every element of the US military’s story. It questioned, for example, how it would have been possible for the three detainees to have stuffed rags down their throats and then, while choking, managed to raise themselves up to a noose and hang themselves.

Story continues below…

The report (PDF) stated:

There is no explanation of how each of the detainees, much less all three, could have done the following: braided a noose by tearing up his sheets and/or clothing, made a mannequin of himself so it would appear to the guards he was asleep in his cell, hung sheets to block vision into the cell—a violation of Standard Operating Procedures, tied his feet together, tied his hands together, hung the noose from the metal mesh of the cell wall and/or ceiling, climbed up on to the sink, put the noose around his neck and released his weight to result in death by strangulation, hanged until dead and hung for at least two hours completely unnoticed by guards.

A SECRET FACILITY

Army Staff Sergeant Joseph Hickman told Harper’s magazine that he was made aware of the existence of a secret detention center at Guantanamo, nicknamed by some of the guards “Camp No,” because “No, it doesn’t exist.” According to Hickman, it was generally believed among camp guards that the facility was used by the CIA.

Hickman also said there was a van on site, referred to as the “paddy wagon,” which was allowed to come in and out of the main detention area without going through the usual inspection. On the night of the three detainees’ deaths, Hickman says he saw the paddy wagon leave the area where the three were being detained and head off in the direction of Camp No. The paddy wagon, which can carry only one prisoner at a time in a cage in the back, reportedly made the trip three times.

Hickman says he saw the paddy wagon return and go directly to the medical center. Shortly after, a senior non-commissioned officer, whose name Hickman didn’t know, ordered him to convey a code word to a petty officer. When he did, the petty officer ran off in a panic.

Both Hickman and Specialist Tony Davila told Harper’s that they had been told, initially, that three men died as a result of having rags stuffed down their throats. And in a truly strange turn of events, the whistleblowers say that — even though by the next morning it had become “common knowledge” that the men had died of suicide by stuffing rags down their own throats — the camp commander, Col. Michael Bumgarner, told the guards that the media would “report something different.”

According to independent interviews with soldiers who witnessed the speech, Bumgarner told his audience that “you all know” three prisoners in the Alpha Block at Camp 1 committed suicide during the night by swallowing rags, causing them to choke to death. This was a surprise to no one—even servicemen who had not worked the night before had heard about the rags. But then Bumgarner told those assembled that the media would report something different. It would report that the three prisoners had committed suicide by hanging themselves in their cells. It was important, he said, that servicemen make no comments or suggestions that in any way undermined the official report. He reminded the soldiers and sailors that their phone and email communications were being monitored. The meeting lasted no more than twenty minutes. (Bumgarner has not responded to requests for comment.)

Scott Horton of Harper’s reports: “The presence of a black site at Guantánamo has long been a subject of speculation among lawyers and human-rights activists, and the experience of Sergeant Hickman and other Guantánamo guards compels us to ask whether the three prisoners who died on June 9 were being interrogated by the CIA, and whether their deaths resulted from the grueling techniques the Justice Department had approved for the agency’s use—or from other tortures lacking that sanction.”

Horton’s story “lacks an eye-witness, or a smoking gun,” writes Michael Scherer at Time’s Swampland blog. “But it does raise several questions that should be answered in the coming months, including: Was there a classified interrogation site at the GTMO facility? Were soldiers on the base told by a commanding officer to keep quite about the cause of death (choking on rags) of the three inmates, as multiple soldiers told Horton?”

All three of the detainees who died that night in 2006 were considered “problem prisoners” and were held in an area reserved for detainees who were troublemakers or had high-value information. All three had previously participated in hunger strikes to protest their detention.

When their deaths were announced in June, 2006, Rear Adm. Harry Harris cast the alleged suicides as an act of warfare against the US.

“They have no regard for life, either ours or their own,” he told the media. “I believe this was not an act of desperation, but an act of asymmetrical warfare waged against us.”

Rear Adm. Harris added: “They are smart. They are creative, they are committed.”

http://rawstory.com/2010/01/whistleblowers-gitmo-suicides/

<>

The Story Of A British Muslim Who Lost His Eye At Guantanamo

January 27, 2010

For nearly six years, British resident Omar Deghayes was imprisoned in Guantánamo and subjected to such brutal torture that he lost the sight in one eye. But far from being broken, he fought back to retain his dignity and his sanity.

For nearly six years, British resident Omar Deghayes was imprisoned in Guantánamo and subjected to such brutal torture that he lost the sight in one eye. But far from being broken, he fought back to retain his dignity and his sanity.

How I Fought To Survive Guantánamo

By Patrick Barkham

The Guardian (UK)

21 January 2010

It is not hot stabbing pain that Omar Deghayes remembers from the day a Guantánamo guard blinded him, but the cool sensation of fingers being stabbed deep into his eyeballs. He had joined other prisoners in protesting against a new humiliation – inmates being forced to take off their trousers and walk round in their pants – and a group of guards had entered his cell to punish him. He was held down and bound with chains.

“I didn’t realise what was going on until the guy had pushed his fingers inside my eyes and I could feel the coldness of his fingers. Then I realised he was trying to gouge out my eyes,” Deghayes says. He wanted to scream in agony, but was determined not to give his torturers the satisfaction. Then the officer standing over him instructed the eye-stabber to push harder. “When he pulled his hands out, I remember I couldn’t see anything – I’d lost sight completely in both eyes.” Deghayes was dumped in a cell, fluid streaming from his eyes.

The sight in his left eye returned over the following days, but he is still blind in his right eye. He also has a crooked nose (from being punched by the guards, he says) and a scar across his forefinger (slammed in a prison door), but otherwise this resident of Saltdean, near Brighton, appears relatively unscarred from the more than five years he spent locked in Guantánamo Bay. Two years after his release, he speaks softly and calmly; he has the unlined skin and thick hair of a man younger than his 40 years; he has just remarried and has, for the first time in his life, a firm feeling that his home is on the clifftops of East Sussex.

Deghayes must, however, live with the darkness of Guantánamo for the rest of his days. There are reminders everywhere, from the beautiful picture of Saltdean that was painted for him while he was incarcerated, to the fact that Guantánamo remains open 12 months after Barack Obama vowed to close it within a year.

There are still around 200 prisoners left in the detention camp, many of whom have been there for eight years. Of the 800 freed, only one has been found guilty of any crime and he was convicted by a dubious military commission, a verdict that is likely to be overturned. Deghayes, too, does not want to forget. He says there is so much still to be exposed about the conditions there, and about British collusion in the extraordinary rendition and torture of men such as him in the months following the American-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.

Deghayes, one of five children of a prominent Libyan lawyer, first came to Saltdean from Tripoli aged five, to learn English with his brothers and sisters on their summer holidays. He would return and stay with British families every summer. Then, in 1980, his father, an opponent of the increasingly totalitarian Gaddafi, was taken away by the authorities. Three days later, Deghayes’ uncle was told to collect his body from the morgue. Harassed and increasingly fearful for their safety, Deghayes’ mother sought asylum for her family in Britain. They settled in the place they knew best, Saltdean, in a large white house with fine views over the sea. More than two decades on, the family still lives there.

After a secular upbringing in Saltdean, Deghayes became a practising Muslim while at university in Wolverhampton, where he graduated in law. When he finished studying to become a solicitor, he had a “longing” to return to Libya but couldn’t because of his family name and opposition to Gaddafi, so he left for a round-the-world trip to experience Arabic cultures and visit university friends. He enjoyed Pakistan’s mixture of west and east, and was then tempted into a trip to Afghanistan: he saw business opportunities and the chance to use his languages (Farsi, Arabic and English) and legal training (understanding both western and Sharia law) to help import-export companies.

He fell in love with the country and an Afghani woman; they married and had a son. “I liked the country – such beautiful rivers and different terrains. The people were difficult to get to know at first, but if they knew you and liked you, they’d open their hearts and houses to you,” he says. Afghanistan, it seems, triggered many ambitious dreams: he says he helped set up a school in Kabul, assisted NGOs, experimented with an agricultural social enterprise and exported apples to Peshawar. “I was generating income for myself but I had more ambition than that – to establish myself as a lawyer,” he says. “Things were really good. Then this war broke out and everything was shattered.”

Fearing for his new family’s safety, he paid people-smugglers to get them all back to Pakistan in early 2002 after the US-led invasion of Afghanistan. He hoped his mother would take his wife and child back to England, while he planned to return to Afghanistan and continue his NGO and legal work. “I still thought I had nothing to fear. Even if there was an invasion, there was nothing I had been doing that was illegal.”

They rented a house in Lahore, “far away from the war atmosphere”. But then the Americans began paying large amounts of money to find Arabs who had been in Afghanistan. Suddenly, he was lucrative bounty for the Pakistani authorities. “The atmosphere changed completely. Nice Pakistan turned into a trap,” he says. One day, their house was surrounded by armed police. He was seized, but not taken to a normal police station. Instead he was driven, fast and under heavily armed guard, between secure rooms in hotels and villas. A Kafkaesque nightmare had begun.

Deghayes says he was beaten and interrogated first by Pakistani officials. He thinks the Americans and the Libyans competed to “buy” him from the Pakistanis, and it appears the Americans won: when he was moved from Lahore to Islamabad, a man introduced himself as the head of the CIA’s Libyan section. Taken between hotels by armed guards, Deghayes believes he saw a man who is now listed as a disappeared prisoner: an Italian Moroccan. “I remember seeing him; he was with me in the same car in Islamabad. He came out crying from the meeting, scared; he was saying, ‘No, don’t do this to me.’”

Deghayes also describes meeting a British interrogator when he met the CIA section head for the second time. “I was facing the British man, who introduced himself as Andrew. He spoke in an obvious British accent.” According to Deghayes, Andrew said he was from the intelligence services and wanted to question him.

“I was really annoyed and said, ‘You shouldn’t do this, you’re helping these people – I’m kidnapped, abducted against my will. Your job is to get me out of here. I’m British and if I go back to England, I will take you to court for what you are doing now.’ Andrew was a little bit scared, but he looked at me and said, ‘What case would you bring against me?’ I had nothing in my mind. He said, ‘Listen, if you answer my questions and co-operate with me, I will do my best. I will get you out of there.’”

Deghayes was shown an album of 100 photographs of supposed terrorists. He says he did not recognise anyone. One morning, he was tied, bound and blindfolded and taken to an airport. The “thin black bag” was removed from his head: he was standing in front of a mirror, guarded by two US soldiers. They tied another bag over his head, which “felt worse than the first bag – it suffocated me.” It smelt “like socks or cheese,” he says. “This was an indication of the new regime – there were even harder times coming up.”

Inside the plane, it was mayhem: his feet and hands bound together and covered in bags, Deghayes was bundled on top of others in the hold. “People were crying. People were throwing up. Some people were suffocating, and there was a kick here and a kick there: ‘Get your head down, you bastard!’ Things like that. Then the plane took off and you could smell [the guards] drinking spirits.”

They landed in what he later realised was Bagram military air base. Here, Deghayes’ clothes were taken away and he was given two pieces of blue uniform. He was not allowed to speak to fellow inmates, and was bound to barbed wire before, he says, being beaten and made to suffer “all sorts of humiliation”. He spent several months there. “There were no rules in Bagram; people just went in and kicked people if they didn’t like them.”

He says he did not eat for more than 50 days. “I was really sick; I became a skeleton. I couldn’t walk any more. I lost my mind – I was really scared for my mental safety. I tried to eat but I threw up. I started to hear voices in my head because of the hunger. People would say something and I could not understand what they were saying. You hear shouts and you’re speaking to yourself inside your head. I started to become really scared because I thought I was losing my brains and going crazy.”

While he was in Bagram, he was again interrogated several times by officials he believes were from Britain. “They felt I was lying to them. I said to them I studied in Holborn, London. They said, ‘Which train did you take to get there?’ They didn’t believe anything,” he says. “They weren’t free to do what they liked; the Americans were running the show.” When he said he was too sick to speak, they called him “a bandit”.

His British interrogators “came up with lots of stupid things” – suggesting the scubadiving lessons he had taken in the shabby lido in Saltdean, within yards of his family home, were terrorist training. “The Americans took that up in Guantánamo. It was a big headache. They showed me books of military scubadiving and ships and mines and they said, ‘Which ones did you see?’” The British also accused him of teaching people to fight in terrorist training camps in Chechnya, and claimed they had secret video evidence.

Deghayes had never been to Chechnya, and thought all these allegations laughable. Only later did he discover through Clive Stafford Smith, director of the human rights charity Reprieve, that his apparent appearance in an Islamic terrorist training video in Chechnya was the crucial evidence in a flimsy case against him. The authorities refused to give Stafford Smith, who campaigned for Guantánamo detainees, a copy of this videotape, but he eventually obtained one through the BBC.

It was, says the Reprieve director, an obvious case of mistaken identity: the person depicted lacked Deghayes’ small childhood scar on his face. Stafford Smith was able to show that the videotape was of a completely different person, actually a Chechnyan rebel called Abu Walid, who was dead. “This was typical of the whole Guantánamo experience,” says Stafford Smith. “They said they had evidence and they wouldn’t let you see it. Then when you did, it was incorrect.”

After two months in Bagram, Deghayes was flown to Guantánamo in autumn 2002. There, prisoners were treated brutally. According to Deghayes, when guards physically subdued them by tying them down, they would “do actions to pretend as if they are raping you. They put you down on your stomach. It was really horrible, all sexual and psychological stuff.” On other occasions, he says, guards would hold a prisoner’s head and “bang it on the floor”.

Deghayes developed a personal policy of resistance. Guards would typically arrive at a prisoner’s cell and spray pepper and other chemicals through the “bean-hole”, the hatch in the door. While most prisoners cowered at the back of their cell, Deghayes says he would grab the guards’ hands and attack them. He fought back, as viciously as he could, trying to take the fights with guards out of the privacy of his cell and into the corridors.

“It was chaos; they would fall on top of each other and it was embarrassing [for them]. They were wearing all this heavy stuff [body armour] which didn’t help either,” he says. Some guards became afraid of going into his cell. Most, he says, were Puerto Rican and were not driven by the patriotism of the “war on terror”. They did not want to get hurt for their meagre wages.

Deghayes did not realise how badly his eye had been beaten until a year after the incident, when he looked in a mirror for the first time in four years. He accepts his resistance caused him more physical pain, but believes it subsequently helped him. In the camp, he was less fearful.

“I was targeted more, but I was also relaxed compared with others who didn’t do that. It was really scary for [the guards] to come into my cell,” he says. “Being humiliated by getting beaten up is better than giving your own trousers out. If I’d done those things, I would’ve been really bitter now. I’m probably less bitter than anyone else because I know I gave them a really hard time. If I had given in, and all this was bottled up, I would have been like I see them [other ex-prisoners] – really bitter, full of hatred.”

Deghayes says his suffering made his faith stronger; it helped him survive. “We knew there’s a Muslim [God] behind things, there’s a hereafter, our patience and hardships will be rewarded and the pain has to end sometime. Our religion teaches these things – the good always prevails and the bad is only temporary; the patience of Job, the patience of Moses. All these teachings make a difference.” Praying five times a day delivered transcendence, removing him from the material world of bodily suffering. “My body and physical being can be chained, can be tarnished, can be beaten, can be raped,” he says now, “but not the spiritual: that is something that nobody can bind down. The spirit is what makes us who we are.”